The Blue Maid in Borough High Street reopened under its original name thanks to a joint venture between Brighton’s Unbarred Brewery and Dav Sahota, the owner of the Fatto a Mano pizza chain.

It had taken a couple of years to acquire and refurbish an historic 16th century pub that had failed to emerge from the first lockdown of 2020, and it took a brewer to do it. But it’s not a tied house in the conventional sense.

On opening night, only four of 16 taps were pouring Unbarred. The rest, chosen by manager Simon Wallen, showcased some of the country’s most respected craft brewers: Deya, The Kernel, Burning Sky, Verdant, Elusive, Five Points, Howling Hops, Bristol Beer Factory, Vault City, Anspach & Hobday.

You don’t see much of Unbarred beers in the capital. As its founder Jordan Mower explains, “there are so many tied pubs, so few free taps available to us, and this is a way of getting our beers on the bar, securing sales and showcasing what we do”.

He continues: “But we don’t want to force our brand on people. The public leads when it comes to the beer range.”

A brief history of the brewer-operator

Beer and pubs have always been tightly intertwined but it wasn’t until the industrialisation of brewing in the 19th century that brewers came to rely on tying pubs to their products to secure volume and keep their mash tuns busy.

To begin with, these pubs were almost always rented to tenant operators but, between the 20th century’s world wars, there was a turn towards direct management as brewers introduced retail disciplines and broadened the offer to attract a wider audience in what was known as the ‘improved pub’.

Following consolidation, by the 1960s, pub ownership was dominated by the ‘Big Six’ national brewers leading to a series of government inquiries into to the tied house system that culminated in the 1989 Beer Orders that compelled the major brewers to sell off a total of 11,000 pubs.

This reflected and reinforced a growing feeling the industry would be more profitable if production and retail were separate, and companies concentrated on one or the other. With the exception of what was to become Heineken, every big brewer eventually exited pubs – Marston’s sale of its brewing interests to Carlsberg is just the latest example.

Some family brewers also made the decision to focus exclusively on beer or pubs, but others stuck determinedly with the model that had served them well and have gone on to prove that a tied estate can be an effective bulwark against pressures from both global brewing and the rise of the micros.

The Blue Maid is just the latest example of the variety of ways brewers are now experimenting with a tied house model that has been the bedrock of Britain’s brewing industry for a century or two.

Family brewers, along with Greene King and Heineken (in the guise of Star Pubs & Bars) continue to be great exponents of vertical integration, as it’s sometimes known, providing their own routes to market, and they enjoyed a strong showing at the 2025 Publican Awards.

Hall & Woodhouse, around since 1777, demonstrated how it could move with the times by winning the title of Best Managed Pub Company after opening a series of spectacular new-builds over the past decade, while St Austell was named Best Brewing Pub Company.

Now the family brewers been joined by a new wave of brewer-operators that have seen the value not just in securing steady sales but in guaranteeing quality, showcasing their beers, engaging with drinkers and strengthening their communities. And they’re finding new ways to do it.

Thornbridge Brewery

Based in Derbyshire, Thornbridge opened its first pub shortly after it was founded, two decades ago. It now has eight pubs, operated as two parallel estates. There are five directly managed community houses in and around Sheffield and three under the Thornbridge & Co joint venture with beer importer Pivovar. The latter is set to double its number this year.

“It’s a diverse estate,” declares co-founder and chief executive Simon Webster. “We want people to think of each of them as ‘my pub’ with their own identity. In Sheffield, we’re part of the community now and we’ve got to be open for them.

“Beer is at the forefront. Quality is important and people love choice. We are also cask-led, the handpumps are the first thing you see when you walk in. And you can buy a pint for under £5. You need that affordability and to create a ladder – right up to our barrel-aged stout, Necessary Evil.

“Our first Enterprise Inns lease, the Greystones in 2010, showed us how important it is to have neighbourhood pubs serving a choice of beers. We were free-of-tie on cask, and we were six-deep at the bar on the first night.”

The joint venture with Pivovar began in 2018 with the Market Cat in York. It was followed by the Bankers Cat in Leeds and the Colmore in Birmingham, taking Thornbridge well outside its heartland.

And that expansion is set to continue with three more in the pipeline: the Wild Swan in London’s Fetter Lane, the Fargate in the centre of Sheffield and a converted station ticket hall in Hull.

“They are all opportunities that have taken time to come through,” explains Webster. “It’s been five and a half years since we opened our last pub and seven years since we found the Hull site. We’d like to get some easier wins now and do a couple a year but no more community pubs.

“Thornbridge & Co is a nice model, it works well, and we enjoy them. They have to look right and are built to withstand high volume. Pivovar is a wonderful operator and it brings some great beers. Around 60% of the bar is still Thornbridge, though.

“It’s like the old family brewery model. My son is working in the Bakewell taproom and we now employ the children of people who worked for us originally.”

Titanic Brewery

After 40 years in the game, Titanic Brewery is now part of the family brewer establishment and its own houses have played their part in its success from the start.

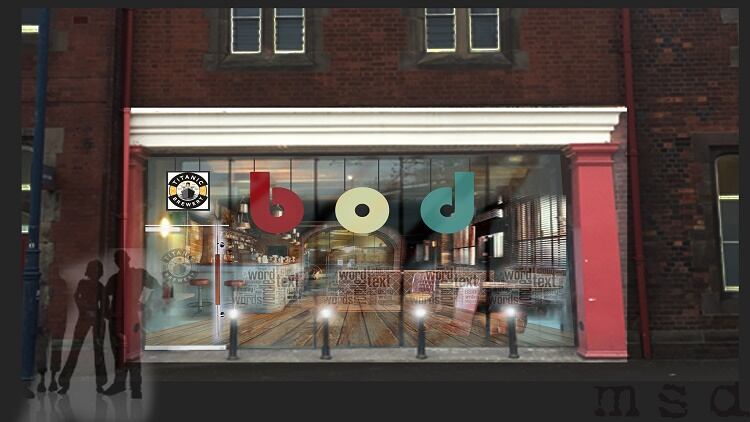

Yet in the past few years, it has introduced a surprising innovation, opening eight Bod all-day café bars alongside its nine traditional pubs around the Midlands.

While there are guest beers from local brewers at each of its sites, according to head of retail Jonathan Wright, Titanic has been surprised at just how far its reputation has spread.

“Our latest pub, the Beacon in Lichfield, Staffordshire, has been amazing. We didn’t realise the power of our beer – that people will come for Titanic ale at a pub so far from the brewery. We’re a small brewer but we’re well known.

“And it’s important our pubs are community hubs, too. Each site has a community noticeboard, including the Bods.”

The first Bod opened in Stafford five years ago. “At that point, we couldn’t open our pubs until midday, so we came up with a concept that we could open at 8am or 8.30am.

“Each Bod tailored to its local environment and the average bar is 65% wet. We’ve recently stopped offering a full food menu at 3pm. After that, there’s a pizza menu that can be prepared by bar staff. That’s helped save costs without losing any trade.

“We can do more to refine the Bod brand. They’ve taken a while to bed in, people have got to get used to the concept but it’s working. Some 17,000 customers have signed up to the loyalty app we launched at the end of last year. That shows the strength in our community.

“We have two or three more Bods in the pipeline, including one on a new housing development in Lichfield,” he adds. “Developers come to us because they see an all-day demand and they like the concept.”

That’s not the only direction Wright sees the company going, though. Titanic has five pubs that sell no food at all, and “we want to grow our wet estate, they’re less complicated, lower cost.”

Vocation Brewery

It was Vocation Brewery’s remote location on a hill outside Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire, that caused it to open its first craft beer bar in the centre of town in 2017.

“We wanted a presence in the local community,” explains operations director Mike Wardell. “It was only a small taproom but it gave us a connection, an engagement with people. Now it’s been extended and we’ve introduced food there – food is playing an important role for us now.”

Three more bars followed, in Manchester in 2021, Halifax in 2022 and Sheffield in 2023.

For Wardell, “it’s about defining what we are. Our bars should be a positive representation of the brewery. Customers are coming to us for an experience, not just a pint. We should be asking how do we engage with them? How do we win their loyalty, their support? How do the bars support the brand? We’re doing a lot of work around that.

“Variety and choice are key,” he says. “Our target is to make sure 65% of sales are our own. There’s a lot of NPD going on in the brewery and we want to show new products. But we also work with like-minded producers and the range varies month by month, offering almost every style of beer. Cask is still important for us, too, and we have five handpumps on the bar.

“It’s not just about the beer, though. We want to have a broad appeal. Craft beer bars can be dark and heavy, we bring brightness and lightness. It feels accessible.

“There’s a lot of focus on the design concept, the look and feel, how we bring the brewery into that in a nice way. It’s about the physical place, how it shows what we stand for, our core values, innovation, bold flavours.”

He’s proud that Vocation has been able to appeal to a broad age range, attracting different audiences at different times of the day.

“We sell more cask ale at lunchtimes while, after work and at weekends, it’s groups of friends who want to try something new and we help them navigate the offer. We’re now hosting monthly beer tasting events around styles and new products. It’s educational and enjoyable, a reason to come out.

“The bars give us a direct communication with the consumer. We can test and trial things, such as our new Hilltop Lager. We trialled the recipe, got feedback, tweaked it. It’s incredibly important to be able to do that, and it gives us customer engagement, too.”

Vocation is now looking to expand at two or three more sites.

Vaulkhard Group

The brewer-operator model isn’t always achieved by a brewery taking on pubs. In Vaulkhard’s case, the Newcastle-based company last year took over local craft brewer Wylam to give its 16 pubs and bars their own range of beers.

It was part of a big change of direction for founder-director Ollie Vaulkhard and his brother Harry.

Ollie states: “We were focused on late-night. It was very profitable, but we weren’t enjoying it. We realised we wanted a different kind of business – modern day pubs in quality environments, driven by quality liquid.

“Harry and I are committed to the region and beer fits into that eco-system of ‘local’ and ‘quality’. We wanted our own brewery, wanted to look after our own kit, so we wouldn’t be obliged to anyone. We could be unique, have drinks others didn’t sell. It’s going back to a true freehouse pub.

“Wylam was already a supplier. It’s been in Newcastle for 25 years and people like the fact it’s local, they want to feel the provenance.”

Becoming a brewer was a step into “a brave new world”, one where Vaulkhard has split with its former supplier Heineken and taken Beavertown Neck Oil, among others, off the bar – “and all without dropping a penny in sales”.

The splendid taproom in Exhibition Park is being extended outdoors and second taproom will be opening in the city centre late summer, Vaulkhard reports, while Wylam has itself seen a big lift in volumes that means it could be needing a new brewery in a few years, he reckons.

McMullen

As the UK beer market has changed and shrunk in volume, family brewers have found themselves with huge breweries that no longer fit what’s needed. Some have survived and thrived through scaling back production while maintaining their brewing heritage and continuing to give their pubs a point of difference.

One is Hertford’s McMullen, which moved across the road from its original Victorian home to a smaller, more efficient, brewery in 2002. Managing director Tom McMullen sums up the reasoning:

“It allowed production to continue in Hertford, using the same chalk aquifer but with greater focus and lower operating costs while the freetrade business, which had been slowing down, was stopped and beer produced exclusively for our own estate.

“Our focus could be entirely on operating the pubs well, either directly, as managed businesses, or by supporting our partners in our tenanted and leased sites.

“We see investing in our pubs is investing in our brewery,” he continues. “We have spent nearly 200 years and millions of pounds building our route to market to ensure we can sell our beer in a profitable manner.

“The brewery, in turn, provides a point of difference for our pubs. Around 21% of volume is own-brewed and the rest of the range is selected to suit each pub. Some of our best volume houses are recent large-scale acquisitions in London. In the Old Bank of England, our beers have a 40% share.

“But the focus is not on volume as such, it’s on quality, innovation, margin, and having the equipment and team in place to quickly adapt to changing consumer tastes.”

To that end – while McMullen’s biggest seller remains AK mild – as keg has overtaken cask production, it has introduced craft lines under the Rivertown umbrella.

Tom McMullen is a vigorous defender of the tie, believing family brewers have “earned the right to supply our own pubs”.

He adds: “Retaining the brewery gives us unity across the pub estate and an understanding of the changing cost dynamics of beer production when negotiating supply with bigger brewers.

“It also demonstrates a loyalty to Hertford’s brewing history and to those who work in this part of our business, and our shareholders are proud that brewing beer is a fundamental component of our trade.”