Pubs that brew their own beer have a long history. Go back far enough and you’ll find the origins of the modern pub as an outlet for somebody’s home brew.

More recently, the 1980s saw a revival in what became known as the brewpub, on the back of the Campaign for Real Ale’s (CAMRA) promotion of cask ale, and again, over the past decade or so, the rise of craft beer has driven a new wave of brewpubs inspired by the American take on the concept.

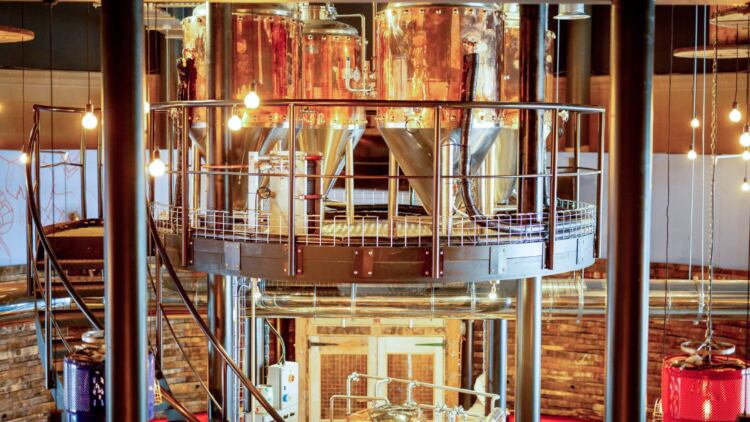

Rather than being hidden away in a cellar or a shed out the back, gleaming stainless steel brewkits take a proud position in full customer view. People enjoy the idea of drinking a beer made just a few feet from where they’re sitting.

Brewing on-site has clear advantages for the publican. It’s a point of difference, selling beers the competition can’t have, and the profit margins are mouth-watering.

Scheme leads to awards

Richard Cook, head brewer at Brewhouse & Kitchen, Bedford

“I started with B&K in Bournemouth in 2017, starting behind the bar. I had an interest in beer, but no real knowledge or experience about craft beer or brewing.

“During three weeks’ training, we were given in-depth knowledge about the different beers we sold, as well as tasting them. That, and meeting the head brewer there, made me fall in love with beer and the industry.

“I shadowed our brewer every day and learned as I went, with the occasional slightly nerve-racking week or two brewing alone when he was on holiday!

“In June last year, I had the opportunity to become head brewer in Bedford and I took it without hesitation because I was raring to get going in my own site.

“Since then I’ve won two awards for my beers from the Society of Independent Brewers and had a couple of spells overseeing our site in Milton Keynes when they were between brewers.

“I’ve felt myself go from strength to strength, as a person and in the job itself, and I feel this is very much down to the apprenticeship scheme, which set me on the right track, as well as the trust placed in me over the past 18 months or so.”

Moving volume

But installing and operating a brewery is no small challenge.

“What you’ve got to ask yourself is what you’re trying to achieve?” says brewing historian Peter Haydon, who ran the Head in a Hat brewery at the Florence pub in Herne Hill, south London, until 2015. “If you’re just in it for some fun you’ve got more flexibility, but if it’s going to be a livelihood for somebody you’ve got to sell enough.

“The late brewer and journalist Peter Ogie calculated you need to sell 10 barrels per person employed per week, though I think that might have gone up to maybe 12 barrels now.

“So I wouldn’t do it speculatively. You must be 100% confident you have the volumes.

“The pub will take a percentage of what you brew but you’re probably going to have to sell elsewhere as well. If you have sister pubs, it makes sense.

“And what are you trying to brew? If it’s cask ale you need to guarantee sales and have close control over the quality. If it’s lager and keg ales, you need more equipment and more sophisticated kit, more budget and more space.”

Another important question is: who’s going to do the work? In Haydon’s experience brewing is so time-consuming it can’t be a part-time job, “and there’s a danger that if you’re not in the brewery, you’re not looking after the quality”.

Whether you plan to brew yourself or employ someone to do it, Brian Yorston, former head brewer at Wadworth and Thwaites, now course manager at the Brewlab brewing school in Sunderland, recommends hands-on experience at a brewpub before you start.

“You’ll find people very co-operative and happy to talk about what they’re doing,” he explains. “Some go into brewing without understanding it – and it’s hard work. A brew day is seven hours long.

“The good thing about brewing for your own pub, though, is that you don’t have to sell it in, and that’s half the battle.

"You’ve got a ready market. There are no distribution costs, and as a small brewer you’re paying half the duty rate.”

Brewer appeal

Sly Beast Brewery at the Ram Inn, Wandsworth, south London

Young’s multiple tenants Keris and Lee De Villiers took over the long-closed Ram Inn last year and, with David Dooley, launched Sly Beast Brewery, which they own between them.

A six-barrel brewkit, plus three conical fermenters, all supplied and installed by PBC, gleams behind glass in a corner of the bar.

“The space made the decision for us on the kit,” says Dooley. “We wanted it to be impressive and functional. We can increase capacity by adding conditioning tanks at the side of the pub but we want to get it right first.”

Responsible for that is head brewer Alexis Leclere. From northern France, where he developed a taste for Belgian beers, he came to London six years ago.

“I realised craft beer was happening so I thought I’d give brewing a go,” he says. “I got a job cask-washing at Wandsworth brewery Sambrook’s – and I think I must have asked too many questions.”

He gained his ‘general certificate’ from the Institute of Brewing & Distilling and later joined Partizan Brewing in Bermondsey, south London, where he explored the “more experimental side” of the craft.

His first beer was a session pale ale named 1533, the year the Ram Inn first opened – the pub had its own brewery back then, too. He’s also produced a porter for the winter, called 4 Foot 2 after the gauge of a local railway, and a spiced 6% ABV Christmas beer, Stargazer.

A Belgian-style pale ale is on the way, “but it won’t be a Belgian strength,” he says.

Most production goes into keg, though the porter is also available on cask.

“We want Alex to produce a consistent core range plus a fun side,” explains Keris. “Within that he has free rein to come up with what he wants. We’ve kept the 100-litre kit we had at another pub for him to experiment on.

She adds: “Brewing on-site, the theatre of it and having local beers taps into a huge trend. We’re celebrating Young’s brewing heritage.”

Brewing akin to cookery

Thanks to the craft beer revolution, there’s a global brewer shortage at the moment so the best solution may be to find an enthusiastic member of staff – perhaps in the kitchen as brewing is really a species of cookery – and train them.

There are a number of schools around the country. Brewlab, for instance, offers a start-up brewing course over three or four days.

“It’s mostly hands-on experience and we can also advise on a business plan and marketing, and how to build a recipe,” says Yorston.

Training programme

Fast becoming the brewpub expert in the UK is Brewhouse & Kitchen (B&K), currently operating 22 pubs across the country, each with its own brewery, varying in brew length from 2.5 to six barrels.

A brewer on each site reports to the pub’s general manager and, as well as making beer, helps deliver beer knowledge to bar staff and customers.

“Recruitment is a challenge,” admits Hayley Connor, the head of people and learning, but the company has addressed that by helping to design a new level 4 brewing apprenticeship that gives it a talent pipeline. Nine employees are currently on the 18-month programme.

“We have around eight spaces a year for apprentice brewers and love people who have a passion for beer and experience in hospitality to apply.

“We’ve also recruited externally, offering training for brewers stepping out of university or technically advanced home brewers.

“For us, it’s about offering a fun work environment, a support network of other brewers and industry-advancing work experiences,” she adds. “Our brewers get a lot of variety in their roles and they are very much the director of their own B&K brewery.

“Our advice to anyone starting out in the brewpub world is to focus on quality,” Connor concludes. “This starts with hiring and training your brewer.

“We recommend using the apprenticeship scheme. It’s a standard developed by employers for employers and is a stamp of quality.”

Get your kit on

How much do you need to spend on brewing equipment? How much have you got?

If you’re a beginner, you might want to start on something small on which you can experiment with recipes and find out whether it suits you and your business.

For little more than £1,000 you can buy an all-grain kit, such as Grainfather, which makes 30 litres at a time using, basically, the same processes as a commercial brewery.

There’s also a kit on the market, the Craftmaster Digibrew, that’s been designed specifically for pubs that want to try brewing their own, conveniently producing a firkin of beer at a time.

From there, you can upgrade to something larger and more sophisticated. Typically, you’ll need a mash tun, a copper and fermenting vessels. Don’t forget casks and kegs, it’s probably best to hire them.

One decision you have to make is whether you want to stick with cask beers or move into keg, for which you’ll have to invest in extra kit. The cost of production is also higher – though keg commands a higher price at the bar.