From the Beer Orders of 1989 to the rise of pubcos, the smoking ban, pubs code, ‘the perfect storm’, recession, securitisation, growth in food, beer duty, the high street revolution and the Licensing Act – the impact has been fundamental to today’s pub.

Brigid Simmonds, chief executive of the British Beer & Pub Association (BBPA), says: “Although pubs have been a familiar feature of our towns and villages for generations, there have certainly been big changes to the pub property market over the past 30 years or so.

“The Beer Orders restricted the number of leased and tenanted pubs large breweries could own. This led to the international ownership of some breweries, and the creation of new pub-owning companies. Changes to demographics, pub customers, the smoking ban, and the beer duty escalator have all affected where pubs are located and how they operate.” BBPA statistics reveal that in 1980 there were 69,000 pubs in the UK, with 35,000 tenanted and leased pubs, 14,000 managed pubs owned by brewers, and 20,000 independently owned.

Fast forward to 2017 and pub numbers had dropped to 48,350 . Now, there are 4,000 managed pubs and only 7,000 tenanted and leased pubs owned by brewers. Pub companies own 5,400 managed and 9,300 tenanted pubs, while 22,650 pubs are independent.

Big Six Domination

The 1980s saw the market dominated by the Big Six brewers – Bass, Whitbread, Allied, Grand Metropolitan, Courage and Scottish & Newcastle – owning 33,000 pubs between them.

Early in 1989 a Monopolies & Mergers Commission report recommended brewery pub ownership to be capped at 2,000 per operator. However, when Lord Young, then Secretary of State for Trade & Industry, came to act a few months later, that recommendation was watered down somewhat – in the Supply of Beer (Tied Estate) Order and the Supply of Beer (Loan Ties, Licensed Premises and Wholesale Prices) Order, commonly known as the Beer Orders – to the effect that brewers owning more than 2,000 pubs were told they must dispose of half of their on-licenced premises in excess of that number or dispose of their breweries.

Even so, Fleurets director and head of pubs Simon Hall describes it as the “biggest thing” to affect the industry in its history, and by 1991 the creation of what we know now as the “pubco” had resulted. Enterprise Inns was founded in 1991, while Punch was set up a few years later in 1997. At one point the two pub companies owned more than 20,000 pubs between them.

Before them came Inntrepreneur. Hall says: “These were the first modern pubco and they developed the lease, a partly tied lease, followed by the Vanguard lease, which was the Tetley version of it.”

Paul Davey, managing director of Davey Co, says the Beer Orders were a “catalyst” for a change in the property market.

“They led to the biggest change in the pub market seen in not just 40 years but probably the previous 100 years. It fundamentally shifted the advantage of pub ownership from brewers to tied pubco leases and created the pub company tied leasehold model,” he says.

Benefits of early leases

While the current view of pubco leases has led to further Government intervention, Pubs Code Adjudicator, early leases offered generous terms, usually providing for free-of-tie beer options as well being free for wine, spirits and soft drinks.

“The rents were also not quite so heavy because the disposals through the regional and corporate brewers saw package sales as opposed to a lot of individual sales,” explains Davey. “The pubcos were able to acquire sites at sensible market rates.”

But this situation did not last for long. According to Hall, the entry of Nomura in the late-1990s, purchasing Inntrepreneur and Unique Pub Co, and the securitisation that followed changed the market “seismically’ and was a “game changer” in transactions.

“Individual pub prices shot up and package values rose in some cases by as much as 40% more than the sum of the individual values,” Hall says.

“You were taking a pub income stream and wrapping it in an insurance package and selling it as an investment.

As a result , the freehouse market was plundered by pubcos for a good 15 years as they bought individually and through the nose, then wrapped it in a package to securitise the income stream.”

Davey says that things became so competitive between major pub operators that they were overpaying when buying and acquiring sites.

“It wasn’t just the Beer Orders , it was the consequence and collapsible damage it caused because the pubcos became so greedy for more and more acquisitions. Because they were paying so much money, they had to skew the tied model in their favour to support the capital outlay to buy them,” he says.

The result was that pubcos were in debt and, because the model was unsustainable, they started disposing of pubs.

But the situation with the pub sector did not just revolve around the tenanted and leased sector. In the early ’90s, a revolution on the high street began. Bars such as Yates’ Wine Lodges opened in city centres, and customers were no longer forced to drive to destination pubs.

Advent of the Licensing Act

It was 2005 when the Licensing Act came into force. is also changed the face of the pub property market as nightclubs were now forced to compete with these city-centre bars.

By 2007, a combination of issues dubbed the ‘perfect storm’ – the smoking ban, duty hike on beer that saw the rise of supermarket alcohol sales, and economic turmoil which resulted in the credit crunch – had arrived.

Neil Morgan, managing director for pubs and restaurants at Christie & Co, says that the period from 2007 to 2012 was one of consolidation and mass administrations in the sector.

“We saw mass disposal programmes from the likes of the big pubcos. There were no portfolio buyers then apart from the likes of Admiral and a few others,” he says.

This saw the decline of pubs, with many sold for alternative uses. Morgan additionally puts the dwindling pub market down to the erosion of the UK’s manufacturing and industrial base.

Pubs began focusing on food, with many becoming obsolete due to lack of outside smoking areas and kitchen space.

But while the smoking ban and other factors in the ‘perfect storm’ had a dramatic effect, Morgan says the pub sector has managed to adapt.

“The pub has really evolved and the one thing I would say about the sector as a whole is that whatever gets thrown at it – legislation, economic forces and anything else – it has this ability to adapt and survive,” he argues.

Metamorphosis of pub food

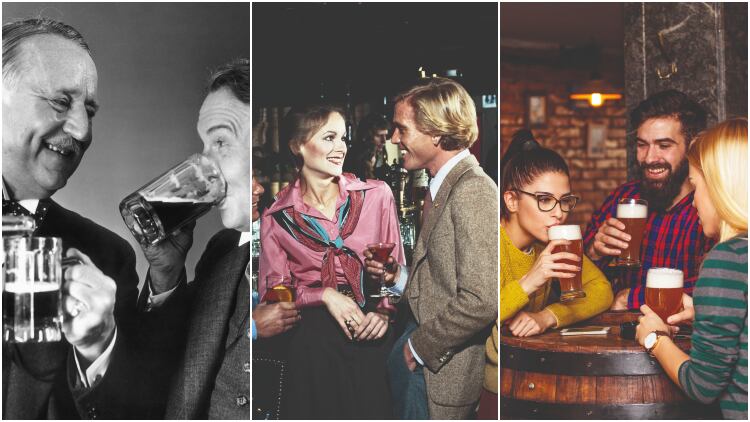

While he admits that 30 years ago the pub food offering was more likely to be sandwiches curling up under a fly net on the bar, or a pickled egg, this too has undergone dramatic change. While Berni Inns was the pioneer of the family pub restaurant, other operators started to follow with the creation of family restaurant chains such as Beefeater.

While the food might be uninspiring compared with some of today’s culinary delights from Michelin-star gastropubs and other high-end outlets, the prawn cocktail, chicken liver paté, chicken in a basket, steak and chips followed by Black Forest gateau on offer then were at the top of their game.

All these changes have led to the pub becoming a more diversified business. While many have moved into food, good wet-led operations still thrive but accommodation and function rooms have become more important, says Morgan.

So to 2016 and the introduction of the Pubs Code, which has had a major impact on the tenanted and leased market. Morgan says that while in the past lease agreements were offered on a ‘take it or leave it’ basis, today’s pubcos have learned to adapt and tailor agreements around the operator.

However, some pubcos have a managed division and within the lease there is a provision that the company has the right to take the lease back. “That can be an issue,” says Morgan. He believes there are still 1,000 pubs to go in the market.

And while many pubs have already closed, it is not all bad news as many operators are building new ones. Dan Mackernan, director at Savills Licensed Leisure and honorary secretary of the Association of Valuers of Licensed Property, says: “No one was building new pubs 30 years ago but now you have new builds from Marston’s, Greene King and, to a lesser extent, Mitchells & Butlers and Whitbread.”

Bigger is now better

The design of these pubs has also changed as they are now bigger and need larger car parks. “It is a big openplan box, but the size has gone to 10,000sq ft needing more than 150 covers and big car parks.”

This also reflects changes in existing pubs, Mackernan says. “Pubs were the traditional lounge bar and public bar, and they had off-sales. This has gone and they’ve all moved to open-plan.”

On the tenanted and leased side, he argues, the property sector has gone “full circle”, with companies offering free-of-tie options, shorter leases, and tenancies more available and on more favourable terms.

The pub property sector is constantly changing. But it has been able to adapt and, while pub numbers continue to drop, the quality of premises continues to improve.

To find out more about pubs for sale, lease and tenancy visit our property site.